To Kavuma John Mary, pollution means loss of life. When he was 19 years old, his family’s house stood next to a trench that was clogged by trash, most of it plastic. After a heavy downpour one evening, the drainage collapsed under the weight of flood waters, which destroyed the house. “I survived with injuries to my head and a broken right arm. However, my only beloved grandmother died from the injuries she suffered. The police report showed that it was the huge accumulation of plastic waste in the trenches near our house that caused the incident. This is where I declared war on plastic waste,” he said. He founded Upcycle Africa, a for-profit start-up that trains marginalised people in Uganda to collect discarded plastic bottles and repurpose them into building materials for affordable houses. They use other types of waste plastics to make handbags, and fuel through a heating process known as pyrolysis.

Kavuma refers to United Nations (UN) reports that warn of the growing plastic crisis around the world. “The challenge that I am trying to solve is plastic waste. The UN warns that by 2050 we shall be having more plastic in the ocean than fish,” he said. Environmentalists also say poor waste management leads to soil infertility since the polyethene and plastics prevent water filtration in the soil, air pollution when the waste is burnt, animal deaths when polyethene are ingested, and flooding since the water channels can be blocked and trap fish and other organisms. Uganda recently reviewed its environment law (the National Environment Act No. 5 2019) and banned all plastic carrier bags under 30 microns. It also imposed producer extended responsibility as part of the polluter pays principle. This tasked the producers of all plastic materials to follow the management of their product through its life cycle.

The government also imposed a requirement that all plastic manufacturers should establish recycling plants and ensure the plastic material they produce is recycled. This is a precondition for licensing any new plastic manufacturing enterprise. But this law is never enforced, and plastic bottles and polythene bags continue to litter Ugandan neighbourhoods. “According to [Uganda’s] National Environmental Management Authority, 600 tons of plastic is produced in Kampala every day. At least 91 percent of this plastic remains uncollected, ending up in waterways, and clogging pipes. I believe that if I get the necessary support I can be able to create the much-needed change that our planet and the people need,” Kavuma said. Upcycle, therefore, sensitises communities on the dangers of plastic waste. Upcycle then hires some of them to collect plastic waste, especially from beaches, streets and bus stations.

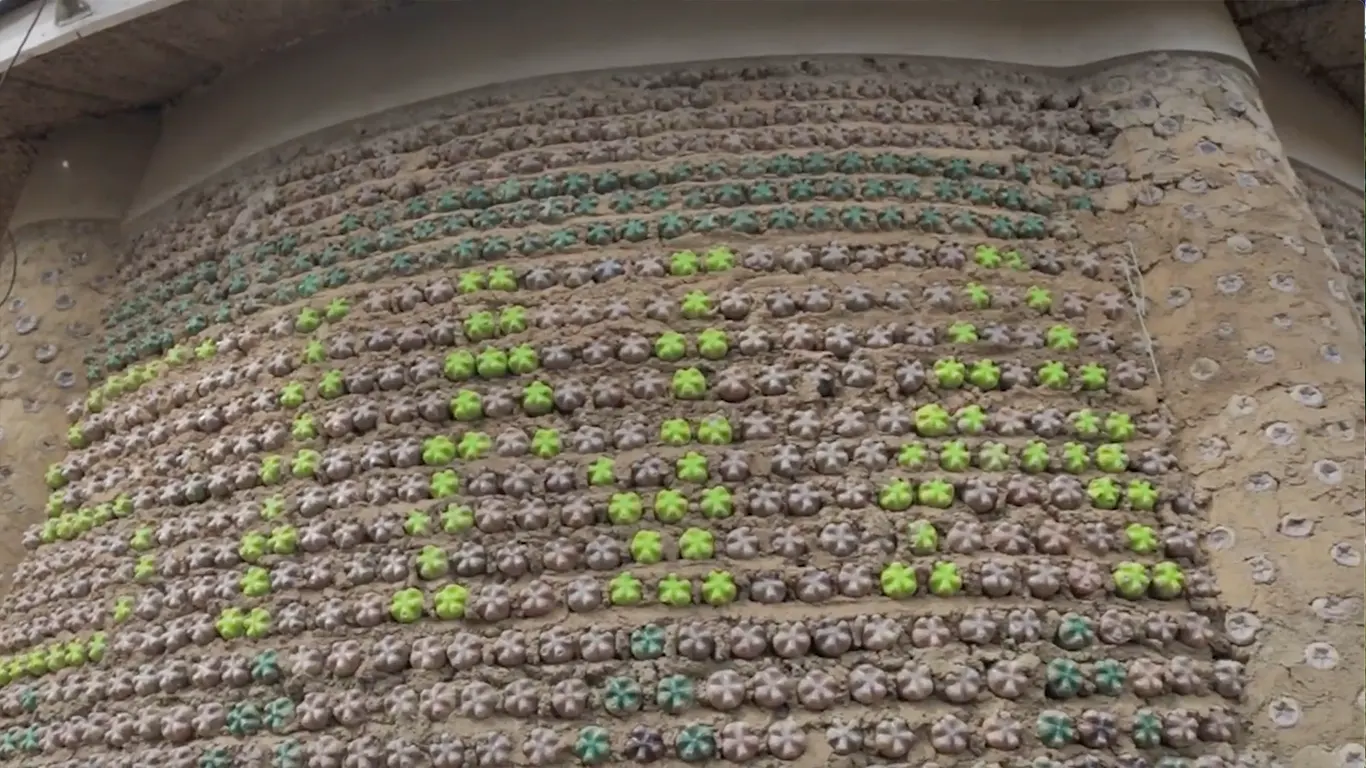

They then fill plastic bottles with soil. The bottles are then laid on mortar and act as bricks in houses. “We all know that plastic waste poses a lot of threats to the environment and human health. So we are doing this by collecting plastic waste, changing people’s mindset as well as making sure that other people are making sure that we promote innovative mindset amongst youth and different marginalised communities,” Kavuma said. He added that as an African entrepreneur, he faces the challenge of low resources, few networking opportunities, the inability to mechanise processes as well as changing people’s mindset about plastic management.

In November last year, Upcycle responded to a call by the Adaptation and Resilience ClimAccelerator for Africa to African entrepreneurs to access technical assistance in form of business advisory and mentorship, investor readiness support and grant to help strengthen their climate solution via EIT Climate-KIC’s second African-wide accelerator. The programme supports innovations that address physical climate risks or build the resilience of local communities in Africa. The company was among the 16 start-ups chosen from 11 African countries. The others are from Benin, Cameroon, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Gambia, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Madagascar, Senegal, and Tanzania. The programme is funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs of Ireland (Irish Aid).

It was implemented by KCIC Consulting Limited (KCL) and Concree SAS who offered access to funding, expertise, and mentorship. Kavuma said the five-month mentorship has helped Upcycle pivot to a different business model and introduce the use of technology in operations. “That has been one of the biggest achievements from the program so far as well as accessing funding,” he says. The company has also begun recycling plastics into fuel. “We recently actually introduced a new project that is turning plastic waste into fuel. And this is the model that we are carrying on and we are looking forward to spreading this model to very many other African countries,” Kavuma said.

“The biggest experience was networking with different likely-minded individuals in the programme as well as using the latest tools to calculate the impact of our work, for example, the impact calculator as well as getting access to funding and different other opportunities,” he added. The mentorship also helped Upcycle scale up to different countries such as Nigeria, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. Some entrepreneurs from South Sudan and Sierra Leone have also expressed interest in adopting the model in their own countries. “So many other things are happening, for example in Kasese where floods are actually killing people and animals, and people lose properties,” he added. “It’s our time to do something and I believe that this is our responsibility. It must be the legacy we leave behind to create a more resilient and more attractive world for the future generation.”